Releases of political prisoners do not translate into freedom and send a message of fear to society, say human rights defenders

A group of family members applauded outside the Tocuyito prison, in the state of Carabobo, on the afternoon of November 16. Fathers and mothers celebrated every time a political prisoner was released. Among them was Jefferson Torres, a visually impaired person detained days after July 28. The cameras of Venezuelans for Information (VPItv), as well as those of the citizens present at the scene, captured the reunion.

Similar scenes occurred just 85 kilometers away, in the Aragua Penitentiary Center, known as Tocorón, where José David Crespo, barely 15 years old, was released from prison after spending 109 days in prison. He had been arrested when he was 14 years old and, by then, he was the youngest of the adolescents arrested in the post-electoral context in the state of Lara, according to the Venezuelan Prisons Observatory.

In total, according to what was announced by the Public Ministry (MP), 225 people were released from prison on November 16 and 17. This is a figure higher than that recorded by the NGO Foro Penal, which has so far recorded the release of 165 political prisoners.

“The Prosecutor’s Office says it is a little more; It is possible that this is the case because there is no official list of those released from prison and this has been handled with great opacity. There has been no concrete and verifiable information from the authorities,” said Gonzalo Himiob, vice president and founder of the Penal Forum, in a telephone conversation with The National.

The releases occur after requests for review of measures that the MP filed before the courts, Himiob explained. However, only public defenders imposed by the authorities have been able to intervene in these proceedings. In the cases that the lawyers of the Penal Forum have been able to verify, All those released have precautionary measures that limit their actions.

In that sense, not only is information not given to the family members, but they are not allowed to have access to their trusted lawyers or to the files.

“The criminal proceedings against them continue and are not, therefore, completely free. That is why we talk about releases and not releases,” Himiob said.

Currently, 1,751 people are still imprisoned for political reasons, according to the Penal Forum. Of that number, 41 are teenagers. Never before had they registered such a high number of political prisoners in the country.

#Carabobo | This was the reunion of Jefferson Torres, one of those released this month #16Nov in the Tocuyito prison, with his family.

Jefferson is a visually impaired person and was arbitrarily detained in the post-election context of the #28Jul.… pic.twitter.com/2ilnp7si9U

— VPITV (@VPITV) November 16, 2024

Under what conditions were the releases of the political prisoners?

The precautionary measures imposed on those released from prison are procedural benefits guaranteed in Venezuelan law. But they establish important limitations, such as having to appear before a court every certain time and not give statements to the media, for example, which ends up once again violating the rights of those released from prison.

This situation has been constantly repeated among all people detained for political reasons, says Rafael Uzcátegui, human rights activist and director of the NGO Peace Laboratory. They are trials that extend for years, without any response, but with a clear intention: to coerce people so that they do not participate in demonstrations or speak out against the national government.

The legal limbo has also forced the released people and their families to be careful with their approaches to the press and even NGOs, which further encourages opacity around the conditions of their releases.

“It is very difficult to obtain testimonies from people who are released from prison. We know that, in some way, they have been told that they cannot say anything about what they experienced while they were detained or anything that has to do with their processes,” Himiob explained.

This combination of factors, in Uzcátegui’s opinion, has become a mechanism of punishment and a message to frighten society: “This is what could happen if people exercise their right to peaceful demonstration or are subject to arbitrary detention.” ”.

“There is a true and clear intention of the government not to know what happened in these criminal proceedings because that is what different international actions that have been carried out are nourished by,” Himiob added.

Venezuelan lawyer Gonzalo Himiob, vice president of the NGO Foro Penal, speaks during a press conference in Caracas on November 14, 2024. Photo: Juan BARRETO/ AFP

Releases do not end the problems

The problems of those deprived of liberty, by no means, end with their releases. They all end up suffering from physical conditions (such as weight loss due to poor diet), emotional conditions (fear of socializing) and mental conditions (post-traumatic stress, anxiety and panic) that end up leaving a profound mark on them.

“Under a country in which the rule of law operates, people could benefit from compensation from the State, or be part of public policies to reverse some of these situations. This should be a task led by the Ombudsman’s Office, which in our case has no independence and is an appendix of the current Attorney General,” says Uzcátegui.

These conditions also extend to family members, whose first reactions when seeing their detained relatives is fear and confusion at what may happen. They live with the expectation that their loved ones can be released, but with the threat from officials who warn them that conditions could worsen if they leave a record of the situation, whether by exposing the cases, protesting or recording a video.

Despite this very adverse scenario, family members find each other, build friendships based on shared pain and form groups to report the situation of each of their relatives.

“Family members are permanently re-victimized and, although the condition of their loved one varies depending on the prison they are in, all of their rights to due process are violated,” concludes Uzcátegui.

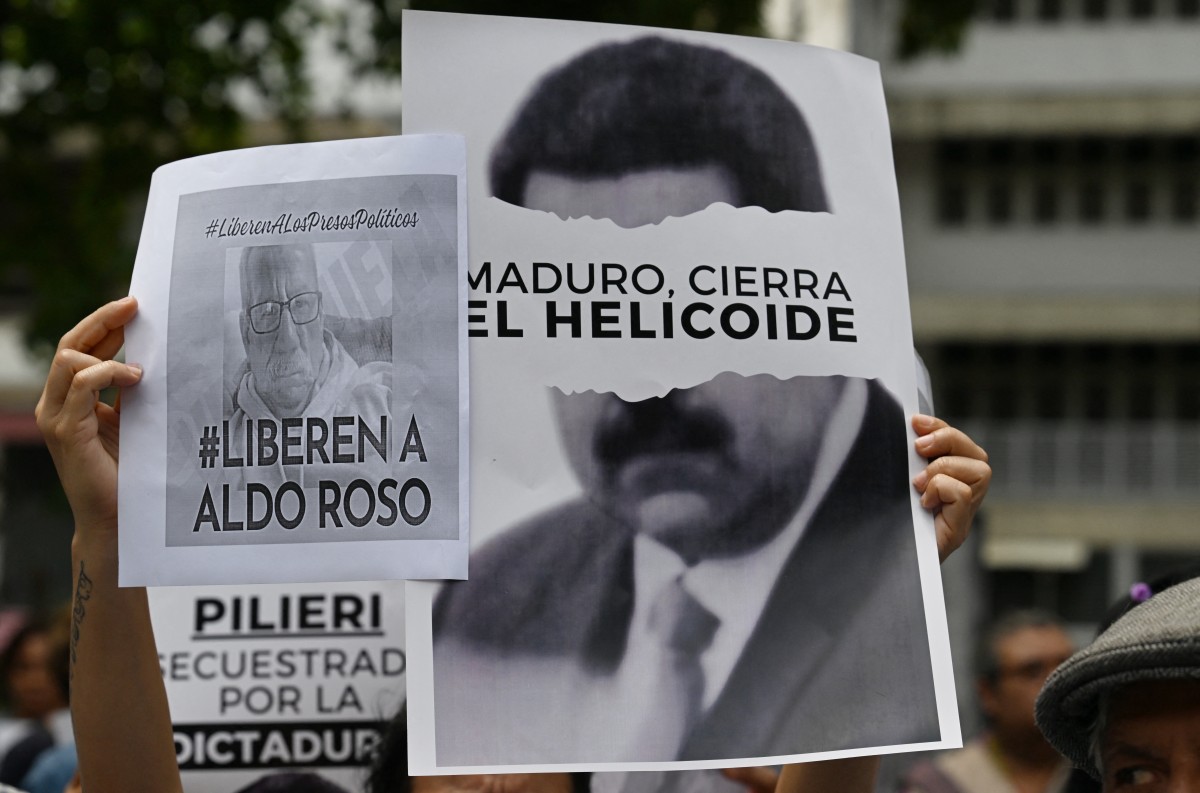

Protesters hold signs against the government of President Nicolás Maduro and demand the freedom of political prisoners during a protest at the Brazilian embassy in Caracas on September 11, 2024. Photo: JUAN BARRETO / AFP

Unprecedented repressive escalation in the country

Himiob and Uzcátegui agree on the existence of levels of government repression that had not been seen before in Venezuela. They assure that it is directly related to the authorities’ intention to avoid any complaint or protest that, in any way, is capable of calling into question the electoral result announced by the National Electoral Council (CNE) on July 28 or violating its permanence. in power.

While the political costs of carrying out repression are high, both nationally and internationally, Himiob believes that The government of Nicolás Maduro is willing to assume them.

“As of January 10 (2025, when the new presidential term begins) they will be a military and police occupation force of Venezuelan territory, whose main public policy will be the use of coercion and force,” Uzcátegui warned.

Related News

Independent journalism needs the support of its readers to continue and ensure that the uncomfortable news they don’t want you to read remains within your reach. Today, with your support, we will continue working hard for censorship-free journalism!